Genetic Testing to Fight Cancer Discussed during DC-Cam 5th Cambodian Medical Students Workshop

Genetic Testing to Fight Cancer Discussed during DC-Cam 5th Cambodian Medical Students Workshop with Dr. Manop Pithukpakorn of Thailand (Clinical Molecular Genetics, American Board of Medical Genetics, 2007-2017, The United States of America)

Phnom Penh — The 5th Cambodian Medical Students Workshop held in Phnom Penh on March 19 focused on a screening approach that would make it possible to identify people prone to cancer well before they are actually affected by the disease.

As Dr. Manop Pithukpakorn, guest speaker at the event, explained, “[i]f we do genetic testing or screening, we have early protection and prevention for those who are at risk of developing cancer because of their genetic factor.”

Because in addition to lifestyle, environmental and nutrition factors, genetic factors may also contribute to developing diseases such cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, he said.

Dr. Pithukpakorn is from Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, (Siriraj Genomics) in Thailand.

Genome sequencing or the study of genome goes back to 1990 when a group of researchers joined in to take part in an international scientific research project on the topic. Completed in 2003, the effort continued at the National Human Genome Research Institute based in United States and through the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium.

In 2019, the Thai government started the Genomics Thailand Project. This made Thailand the first country in the region to do research on genome. The project is based at Siriraj Center of Research for Excellence in Research Medicine (SiCORE) or Siriraj Genomics.

As Dr. Pithukpakorn explained during the workshop, “[g]enetic testing gives us a new perspective on cancer, rather than fear, for prevention of a genetic disorder before complication…We want cancer to be manageable like other diseases by this advancement of technology.”

Genome-based research could provide treatment for a particular patient, improve its efficacy, as well as help understand hereditary risk for his or her descendants through genetic testing, he said.

However, in Cambodia, looking into the genetic history of a family or a person can be difficult, if not impossible, said Kim Sovanndany, the conference coordinator. “It could be hard for the patients who lost their relatives during the Khmer Rouge Regime, not knowing their family health history and therefore their risks of [having the] disease.”

During the event a medical student asked Dr. Pithukpakorn whether genetic testing should be done on an unborn baby. “[I]t is not a scientific matter, but an ethics matter in this case,” he responded. “It should be up to an individual who is over 18 years to decide whether to have genetic testing or not done.”

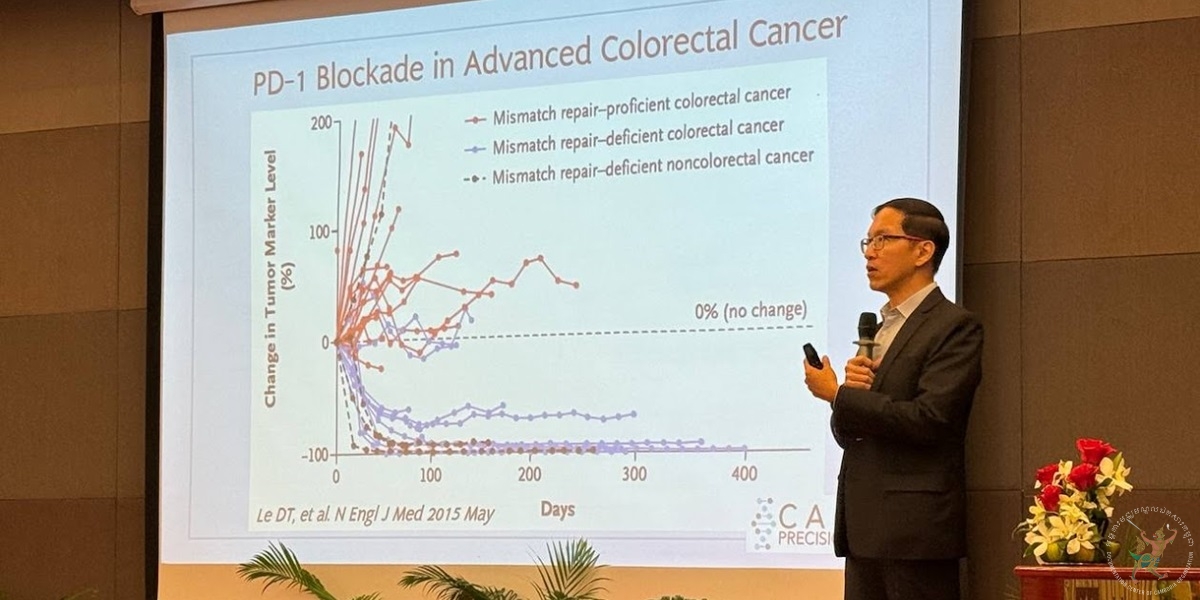

Organized by the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam), the 5th Cambodian Medical Students Workshop was held on the topic of “[c]ancer Precision Medicine, the New Paradigm of Cancer Care.”

Attended by medical students from across the country, it was part of DC-Cam project Advancing the Rights and Improving the Health Conditions of Khmer Rouge Survivors, which is supported by USAID.

The workshop was meant not only for medical students but also for people in Cambodia so they can understand how genome-based research can help deal with cancer in the future, Sovanndany, said. “It is really beneficial, and it is a new subject of study, as genomics is a rare subject in the country.”

As Nov Sovichea, a medical student at the Institute of Health Sciences of the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces, explained, “the benefit of this workshop is about understanding the latest information related to cancer, and genetic testing.”

Ek Chakriya, also from the Institute of Health Sciences, agreed. “[I]t is the first workshop for me that discusses cancer and the genetic factors that contribute to the risk of developing cancer.”

For medical students, she said, “[i]t is an opportunity to consider studying genomics rather than just the fields of study that they knew.”

According to Tuy Kiri, a student at Norton University in Phnom Penh, “[the conference was] an opportunity for the medical students who took part in the workshop to share this new knowledge with friends, relatives and others in our society.”

Beside researching, documenting and building archives on the Khmer Rouge regime of 1975 to 1979, DC-Cam has launched this health education project coordinated by Kim Sovanndany to help bring support for physical as well as emotional healing to those who survived the regime.

“Hopefully, today’s workshop created awareness and showed the advantages of this study to the students who, one day, will be the healthcare providers for patients, and also Khmer Rouge survivors,” she said.

Such workshop, she said, “is for prevention rather than treatment.”

In 2023, DC-Cam published the booklet “Information on the Healthcare of Khmer Rouge Survivors.” This booklet, which is available on the DC-Cam website, mentions that 32,000 survivors, mostly 60 years old and older, have been identified as suffering from 10 of the common diseases.

Text by Sreang Lyhour

Published on March 20, 2024