Khmer Rouge Railways to the Northwest: Young Cambodians Embark on a Historical Journey and Study Tour

Departure at Phnom Penh Railway Station

In the early morning of March 24th, 2024, a group of volunteers was waiting at the train station in Phnom Penh.

They were about to embark on a trip to look into what people went through when they were evacuated from cities and taken by train to remote work camps during the Khmer Rouge regime of April 1975 to January 1979.

The volunteers were part of CamboCorps, an initiative launched in 2021 by the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) whose young members take part in initiatives ranging from helping aging Cambodians who went through that era get the medical care they need, to taking down to their stories of that time to archive it and for them to better understand the country’s recent past.

As DC-Cam had explained in the information on the study tour by train, this trip was meant as an opportunity to comprehend what these forced transfers by train had been for people, how this transfer by train had marked their lives, and also to have the opportunity to travel by train.

On the t-shirts they were wearing was the image of Garuda, which is DC-Cam logo—the mythical creature portrayed as a bird in both in Hinduism and Buddhism, a vigilant protector that, in the DC-Cam logo, looks back to preserve people’s stories, holding a sword in one hand and an Angkear-Bos Flower in the other, represent justice and memory.

The Journey Begins

Thick smoke was released from the chimney as the train left the station. The trip to Mongkol Borey in the northwest of Cambodia was to be about 330 kilometers along the railway built in the early 1930s during the French Protectorate in Cambodia.

According to a Cambodian man who worked on the railway during the Khmer Rouge regime, the railway was repaired with the help of Chinese technicians after the Khmer Rouge forces had captured Phnom Penh.

“After [we] had repaired and reconnected the railway, people were [put on the train and] forced to move from Phnom Penh to Battambang,” he said.

Samut, who is now 75 years old, was assigned in 1975 and 1976 to work as a guard on the train, travelling on the roof. “I also guarded the train during more than 10 transfers from Phnom Penh to Kampong Chhnang, Pursat and Battambang [provinces],” he said.

People forced to travel were from various parts of the country, Samut said. “It was mixed including people from Svay Rieng, but mostly from Phnom Penh who were dropped off at the Boeng Khna station…. They brought the people and dropped them off at various stations, only the top [Khmer Rouge leaders] knew about it…We just followed their orders.”

In the end, around 500,000 people would be transferred to the Northwest Zone. “Those who were killed were mostly from Svay Rieng,” Samut said.

During these forced transfers people’s identities as human beings were dismissed, family members separated without their being able to say a word of farewell.

“Each carriage carried a crowd, from 10 to 15 cargo carriages packed,” Samut said. Those carriages were meant to carry goods and were not equipped for passengers. There also was no food or water for the people on board.

When a carriage was considered full, people would be directed to the next one even when this meant separating family members. The same thing would happen when they were loaded on vehicles when they arrived at their destination.

Asked by a CamboCorps member why people were not trying to escape, Samut said “[h]ow…while [their] family members were still on the train.”

During one trip, people had been killed when the train arrived in Bakan District in Pursat Province, in front of Wat Rumlech pagoda, he said.

The line’s last station at the time was Serei Saophoan in the Khmer Rouge Northwest Zone. And it is in the Northwest zone that the Khmer Rouge would begin in 1977 a purge in their own ranks. “The [Khmer Rouge] regional committees in the Northwest Zone were sent to the S-21,” Samut said, referring to the regime’s extermination camp in Phnom Penh.

Arriving at Sisophon Railway Station, Serei Saophoan City

After an 8-hour journey by train, which felt longer due to the hot weather that affected people on the train, the CamboCorps members reached the first destination, which was Serei Saophoan city in Banteay Meanchey province. They at once went about interviewing Yam Mony, an aging survivor of the Khmer Rouge regime who lived next to the station.

“One day, I sneaked away to visit my parents, but unfortunately the Khmer Rouge caught me,” Mony said.

A few hours later, Mony said, “I was thrown into the flames with other people.” He managed to get out but was hit in the back when a Khmer Rouge threw a knife at him.

Fortunately, Mony was able to hide in the rice paddy until the Khmer Rouge soldiers were gone, he added.

Rice Fields at Preah Net Preah District in Banteay Meanchey province

Near the Wat (Pothi Keo) Preah Net Preah pagoda, the CamboCorps group first met Hong Huy. In 1975, Huy, who was living in Kandal village, was transferred to the nearby village of Kuan Damrei for one month. While there, he saw a whole family being killed. Yern had been deputy commune chief in the early 1970s, that is, during the Lon Nol regime whose army the Khmer Rouge had defeated, enabling them to seize power in April 1975. Killing his whole family was in line with a saying the Khmer Rouge used, which was that to get rid of weeds, one must remove the roots. “Chaiya, a son of Yern was killed in the forest with a hoe… and his sister Kosy was later killed when shot,” Huy said. Another child was killed by a Khmer Rouge cadre who bashed him against a palm tree.

In late 1975, Huy said, people who had been brought by train to the Sisophon station were taken by tractor to work camps in the Preah Net Preah district. “Around 300 to 400 families were moved to Trapeang Veng [village],” he said. Huy and his family were also taken to that village after three months spent in another.

“At that time, people were forced to transfer by train from Takeo, Prey Veng, Akrei Ksat, and Phnom Penh to Battambang, Pursat, and Svay [Serei Saophoan],” he said.

Three members of Huy’s family died during that period: his mother-in-law, his sister-in-law, and his child. “Even though [the Khmer Rouge] did not directly kill them, [they] died due to the lack of medicine and starvation,” Huy said, as the lack was caused by the Khmer Rouge regime.

Song Pharat, who is now 60 years old, had a similar story of killings to share. “At nighttime, people were taken away to be killed,” she said.

Pharat especially remembers four Khmer Rouge—Comrade Han, Comrade Aun, Comrade Morn, and Comrade Ron—who had come from the East Zone and, in the Preah Net Preah district, showed no mercy for people. And some of these four people are still alive, she added.

“People were killed in front of pits,” Pharat said, so that the bodies could be thrown into them afterwards.

Pharat, who was put on farmwork at the time, would work until midnight, she said, with a break of only maybe 30 minutes during the day. “Even if I told them, they wouldn’t believe me,” said Pharat, referring to the younger generation in Cambodia who did not live during the Khmer Rouge regime.

According to Khmer Rouge documents, more than 50,000 people from the East Zone were evacuated. Around 8,000 to 10,000 of the evacuees from the East Zone, including Svay Rieng and Prey Veng provinces, were killed.

In 2015, Im Chaem, who was believed to have been secretary of the Preah Net Preah district during the Khmer Rouge regime, was charged with crimes against humanity, and grave breaches of the Geneva conventions of 1949 at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, that is, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC).

A Story inside Wat Preah Net Preah pagoda

Near the site where people arriving by train were killed by the Khmer Rouge was the Wat Preah Net Preah pagoda, Hong Huy said. “The Khmer Rouge used this pagoda as a health center,” he added.

In front of it, there used to be a rice paddy field, a pond with a waterwheel to irrigate the field in the dry season, said Pharat. “It had been there…for around 100 years,” he said, until the Khmer Rouge destroyed it.

“I was a monk at this pagoda before the Khmer Rouge regime,” said Sal who is 73 years old (he did not mention his family name). “Some stupas from the Sangkum era [Prince Norodom Sihanouk’s regime in the 1960s] are still there.”

The head of the statue of Buddha at the pagoda was chopped off during the Khmer Rouge regime, he said. After the regime, the statue was repaired and painted gold and is still displayed for worship at the pagoda, he said.

Like Huy and Pharat, Sal was transferred to Phnom Sreh village by the Khmer Rouge soldiers.

An Ancient Temple: Banteay Chhmar Temple

On March 25, the CamboCorp group continued its tour with a visit to the Angkorian temple of Banteay Chhmar and its vast site.

The temple was built during the reign of King Jayavarman VII in the late 12th and early 13th centuries. During the civil war in the early 1970s, and then from the 1980s and well into the 2010s, it was heavily looted.

Banteay Chhmar was put on the Tentative List of UNESCO World Heritage Sites at the request of the Cambodian government.

The CamboCorps members were sorry to see the temple so damaged. “As a [Cambodian] youth, as well as a CamboCorps, we should protect and preserve the heritage of our ancestors,” Him Sreyloeng said.

Lao Mala, a CamboCorps member from Stung Treng province, said, “[a]fter visiting the temple, I hope that, if I choose history as my major [at university], I will be able to help preserve our heritage.”

“So, who is responsible for protecting the heritage,” Teh Rofikin asked. Perhaps the answer is all Cambodians together, he said.

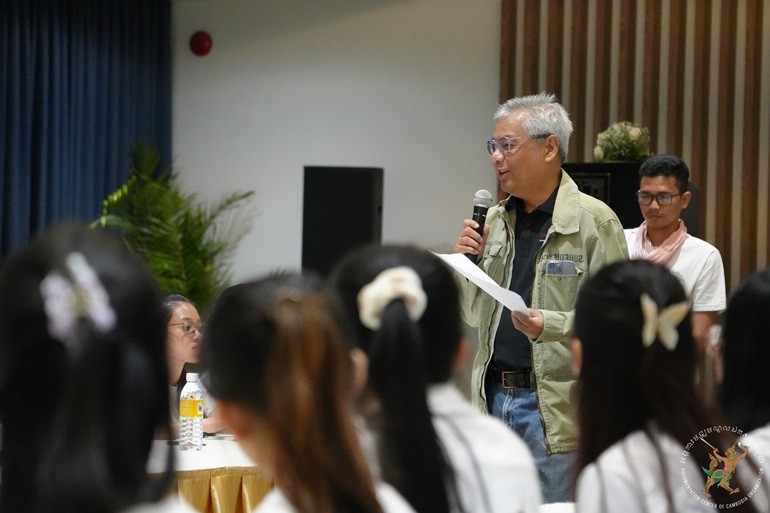

The visit was followed by a meeting with Youk Chhang, executive director of DC-Cam, during which the documentary film “What If the Stones Could Speak” was shown. Afterward, Chhang mentioned the idea of “what if.”

“What if there had been no Khmer Rouge regime,” he asked, raising the issue of what did and what might have happened in the country.

Speaking of what can be done with determination and through peaceful actions since it did happen, even when it looks impossible, Chhang mentioned Indian President Mahatma Gandhi who obtained India’s independence from Great Britain in 1947 through a strategy of non-violence, who insisted on travelling in third class rather than first class on trains, and who had told people “[b]e the change you are trying to create.”

An Old Monk at Wat Rumlech pagoda, Bakan District

During a visit at Wat Rumlech pagoda, Venerable Prak Sarin, who is the head monk and 90 years old, told the CamboCorps members that, prior to the Khmer Rouge regime, he had been a teacher in Pursat province.

When the Lon Nol government took over in 1970, Sarin resigned from his position due to political differences of opinion, he said. He had then moved to Kampot province but had returned to Bakan three years later.

During the Khmer Rouge regime, he said “[m]y sibling’s entire family was killed in Kampot.”

Sarin was arrested in 1977 when he was identified as a former teacher with connections. Fortunately, a man he had helped in the past was working at the detention center. “[H]e helped me survive,” he said.

After the downfall of the Khmer Rouge regime, Sarin first worked as a school principal, and then left to become a monk.

In the Bakan district, more than 10,000 people brought to the area during the Khmer Rouge regime were killed; grave sites were even found on the Rumlech pagoda grounds. A stupa was built at the pagoda in their memory, Sarin said.

As development and infrastructure projects multiply in Cambodia, sites such as the one now marked at the pagoda may be overlooked and built over if not set as historical sites, the CamboCorps members stressed.

Sao Hong, who is from Kep province, said that she had not realized that there was such a site in her province until Khmer Rouge survivors told her about it.

“I’m afraid that if we don’t do anything about these places [to make them] historical sites,” she said, they will be forgotten.

Venerable Sarin admitted having come out of the Khmer Rouge regime traumatized, as many Cambodians have. One woman whose mother was killed at Wat Rumlech has never been able to return to Cambodia. “It affected all of us,” Youk Chhang said.

Role Played by the Train during the 1993 National Elections

Following the signing of the Paris Peace Agreement in 1991, which marked the end of the civil war in Cambodia, the railway from Sisophon to Phnom Penh was repaired so that Cambodians who were in the refugee camps in Thailand could be brought back to Phnom Penh and other cities in Cambodia as part of a United Nations operation. So, from 1992 on, the train, which was dubbed the Sisophon Express, would take 12 hours to bring people from Sisophon city in Banteay Meanchey province near the Thai-Cambodian border to Phnom Penh.

This Sisophon Express also played a vital role during the 1993 National Elections so that people could get home to vote.

The roads were in poor conditions if not mined as a result of the conflict in the 1980s and, since the Khmer Rouge who had signed the 1991 agreement had reneged the peace agreement and were conducting attacks, traveling by train, and under the UN flag was the best option.

According to the book “Chasing the Flame, Sergio Vieira De Mello, and the Fight to Save the World” written by Samantha Power, before the national election of May 1993, more than 370,000 Cambodians were resettled in the country, and more than 90,000 people took the refurbished train from Sisophon to Phnom Penh to cast their votes.

This led the CamboCorps group to discuss the importance of voting, which is part of people’s rights in a democracy and their opportunity to be involved in political decisions. In a democracy, voters are a part of writing history as they choose their leaders. And as said Sergio Vieira De Mello, director of Repatriation and Resettlement Operations of the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) that oversaw Cambodia before the 1993 elections, “[h]istory is not finished.”

In a democracy, every voter plays a role in history.

After the End of the Journey

After traveling by train and listening to the Khmer Rouge survivors, Chhon Na, a CamboCorps from Pursat, said, “I really regretted not believing my grandparents.” This trip and listening to Khmer Rouge survivors along the way had made Na truly realize what people went through during the regime.

On account of German racial purity, the Holocaust took place in the late 1930s through 1945. To achieve a classless society and the “Great Leap Forward” revolution in Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge committed atrocities.

The lives of more than six million Jewish people were lost in Nazi concentration camps in Europe during the Second World War. More than two million Cambodians died in the “killing fields” of Cambodia.

On foot or by boat, truck, tractor, oxcart, or train, every means of transport was used for forced transfer in the country. More than 20,000 burial sites have been found across Cambodia, and also along the railway tracks and stations from Phnom Penh to Mongkol Borey in Banteay Meanchey province.

The first phase of the forced transfer started on April 17, 1975, as soon as the Khmer Rouge had taken control of Phnom Penh. Months later, the second phase took place in the Khmer Rouge central, southwest, west, and east zones, from September 1975 until 1977. In late 1977 to late 1978, the third phase was conducted as a movement of people out of the East Zone.

Genocide and Democracy Study Tours by DC-Cam

Since March 2024, DC-Cam has held eight train study tours for CamboCorps members, the most recent one in April 2024. Each time, the reaction of the young Cambodians taking part in the tours has been similar. As they mentioned in the meetings after the tours, this made them realize the extent of the forced population movements during the regime and the many ways this affected people—those who died and those who survived.

Khmer Rouge Railways: Genocide & Democracy Study Tour for the Youth

The Forced Transfer, the Second Evacuation of People During the Khmer Rouge Regime (1975-1979)

By Lyhour Sreang

Published on April 1, 2024

Interviews by CamboCorps Members